On February 5th, Komsomolskaya Pravda reported that the newspaper's editorial office is relocating to a new building on Pravda Street.

1936

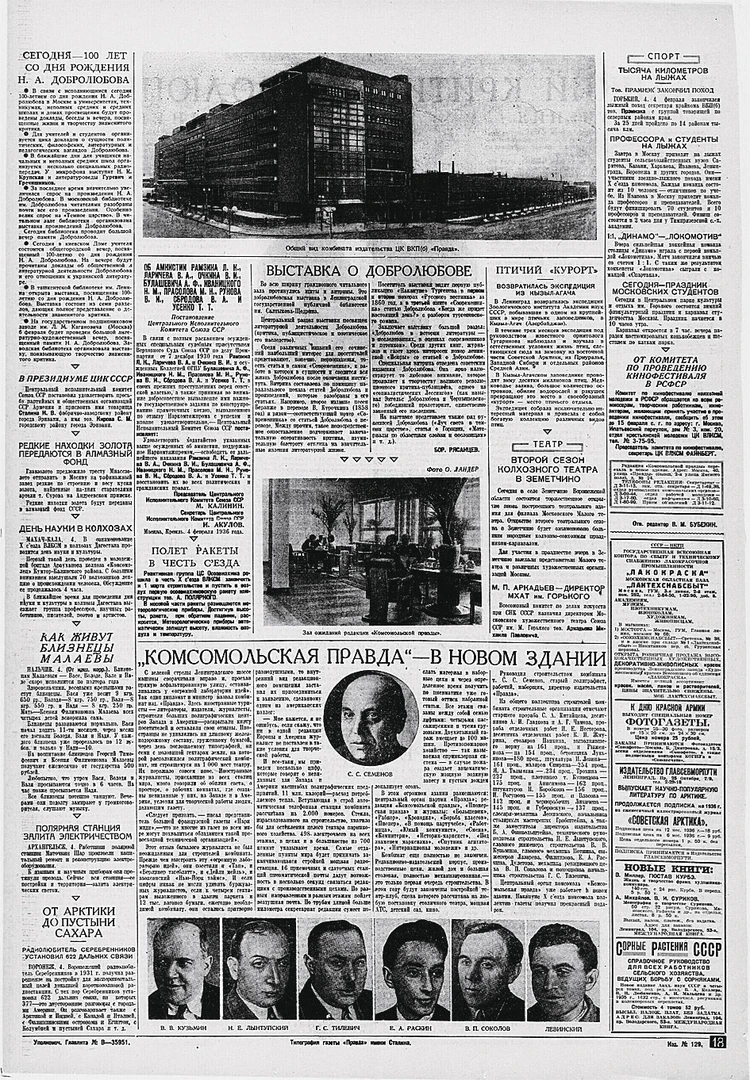

The editorial office of our newspaper was located in the spacious printing and publishing complex "Pravda," where it remained for 70 years (until the fire in 2006). Here, the legendary spirit of the 6th floor was formed, which moved with the team to new offices (even though the floor was different). This is how the marvel of constructivism is described in the latest issue of "Komsomolskaya Pravda":

“From the green arrow of the Leningrad Highway, cars turned left and, after driving along a straight asphalt street, stopped at a ‘huge laboratory of ideas.’ Thus, one diplomat and minister referred to the publishing complex of ‘Pravda.’ Here, foreign tourists—writers, publishers, journalists, builders of large printing centers from the West and America—would open the visitors' book and leave their comments. The foreigners were not surprised by the long train loaded with paper, consumed by the printing house every other day, nor by the seven and a half hectares of land on which the printing complex was situated, nor by the theater under construction with a capacity of 1,000 seats. What amazed them was something entirely different. Foreign journalists, arriving from all the capitals of the world, spoke highly of the abundance of light, the spaciousness, and the working rooms, where unprecedented conditions for creative work were created for the people making the newspaper, conditions they had not seen in the West or America.

“It must be acknowledged,” wrote a representative of the major French newspaper "Paris Midi," “that not many newspapers in the world can boast such an excellent technical organization.”

This comment from an experienced journalist did not come as a surprise to the builders of the complex. Before constructing this ‘huge laboratory of ideas,’ they visited ‘TAN,’ ‘Berliner Tageblatt,’ ‘Daily Mail,’ and the overseas ‘New York Times.’ And while the figures could hardly impress bourgeois journalists—despite the four hectares of laid parquet in the building and 12,000 wagons of paper needed annually by the complex—they remained feignedly indifferent. However, the interior of the editorial room compelled them to join the assertion made by one of their American colleagues:

- I believe I would not be mistaken in saying that in no editorial office in Europe and America is a journalist placed in such conditions for creative work.

“This enormous building houses: the central organ of the party ‘Pravda’; the editorial office of ‘Komsomolskaya Pravda,’ ‘Pionerskaya Pravda,’ and magazines such as: ‘Bolshevik,’ ‘Rabkor,’ ‘Krokodil,’ ‘Class Struggle,’ ‘Pioneer,’ ‘For the Aid of Party Education,’ ‘Worker,’ ‘Young Communist,’ ‘Change,’ ‘Comintern,’ ‘Historian-Marxist,’ ‘Under the Banner of Marxism,’ ‘Agitator’s Satellite,’ ‘International of Youth,’ and others.

“The construction of the complex was led by Comrade S. S. Semenov, an old printing specialist, worker, typesetter, and director of the publishing house ‘Pravda.’

1938

As the headline on the fourth page reports, new lines of the best subway in the world are being built in Moscow:

“Muscovites are eagerly awaiting the opening of new lines of their remarkable underground road. Kursky Station is already connected to the city center. This section is completely ready and will soon accept passengers.

The tunnels of the Gorky radius have been completed to its final station—‘Sokol Settlement.’ The length of this radius is 9.6 km.

Track workers, installers, and electricians have long descended down. Rails have been laid almost along the entire route, and the concrete base is being poured. Finishing works are in full swing at the stations of the radius.

There are six underground palace-stations on the Gorky radius. All of them vary in their design and architectural finishes. The entirely metallic station ‘Mayakovskaya Square,’ despite being at a great depth, impresses with its spaciousness. Instead of the wide pylons typical for deep-lying stations, its arches rest on light metal columns.

The first stage of the metro named after L. M. Kaganovich had a length of 11.6 km. The second stage—14.9 km. The metro builders have already begun work on the construction of the third stage, which will amount to 13.8 km. In 6-7 years, the proletarian capital will receive 40.3 km of the best underground roads in the world.”

2008

Special correspondent of “Komsomolskaya Pravda” Ulyana Skoybeda is investigating a corruption scandal involving three high-ranking security officers from Volgograd:

“When was the last time criminal cases were initiated against the heads of the Main Internal Affairs Directorate?

Answer: not long ago— in 2003, when the head of the Kalmyk police, Timofey Sasykov, was prosecuted (he was convicted for exceeding his official powers and expelled from the service).

But to have the chief of police, the head of the traffic police, and the head of the Ministry of Emergency Situations arrested simultaneously in one region? And for the head of the traffic police to die just a few days after visiting a cell?

Such a carousel of events occurred this year in Volgograd (by the way, a region adjacent to Kalmykia).

What is happening—is a conspiracy among the ranks? Or, on the contrary, is it a conspiracy of organized crime against the ‘ranks’? Or is it simply uncompromising anti-corruption efforts that forced the prosecutor’s office to arrest the heads of almost all law enforcement agencies in a single region?”

“We are racing with Mikhail Tsukruk in his lawyer’s ‘Honda.’ The disgraced head of the Main Internal Affairs Directorate is glad to see the journalist:

- It’s just like Santa Barbara here; we will tell everything! By the way, did someone from the Ministry of Internal Affairs press service call you about me?...

The two-meter general is a remarkable figure. Even before appearing in Volgograd (only talks about his appointment were going on), he managed to get entangled in a story: a local newspaper published an article stating that the candidate for the position of head of the Main Internal Affairs Directorate had previously covered illegal vodka sales, sold timber to China, and embezzled funds... This newspaper, by the way, is the printed organ of the regional administration: meaning that no comma is placed there without the governor’s approval.

The local authorities clearly indicated their position, but the decree on Tsukruk was nonetheless signed (rumors circulated that the general had ‘connections’ in Moscow). And then it all began.

Oh! At his very first press conference, the new head of police announced dismissals: ‘They turned the district departments into a branch of a garbage dump.’

Oh! He hung a poster in the middle of the highway: ‘You can meet with the heads of the Main Internal Affairs Directorate and the traffic police,’ and sat under it...

The general was simply overflowing with ideas. He either created a women’s traffic police battalion or canceled privileged license plates like ‘007’: he ordered them to be placed on garbage trucks, or he proposed to turn the monument to Dzerzhinsky away from the square...”

The criminal case against Tsukruk is thoroughly ‘bureaucratic.’ There are neither stolen funds nor intricate schemes—just administrative resources.

He repaired a thoroughly rotten departmental hospital, but for this necessary and noble cause, for some reason, he took funds not from the budget but from subordinates—the heads of district internal affairs departments. He took them to the medical facility, showed the filthy wards, and delivered a heartfelt speech: ‘Guys, whatever you can contribute...’

They would be in trouble if the ‘guys’ tried to refuse!

Some of the leaders reached out with an outstretched hand to the heads of administrations or businessmen. One contributed personal funds (by the way, 43,000 rubles). And another eight naively robbed their personnel: they withheld 400 to 700 rubles from the meager police salaries...”

In total, they ‘milked’ eight hundred police officers: for a sum of 500,000 rubles (together with the businessmen’s funds, it amounted to over two million). Eighty-eight people were recognized as victims.

The second episode involved three expensive foreign cars purchased by Tsukruk. A ‘Toyota Land Cruiser’—for himself, to drive through rough rural terrain, a BMW