On February 4th, the Komsomolskaya Pravda reported that Yuri Kozlovsky repeated the heroics of Marisyev in 1973.

A few years ago, Yuri Kozlovsky was a guest of "Komsomolskaya Pravda."

Photo: Ivan MAKEEV. Go to the KP Photo Bank

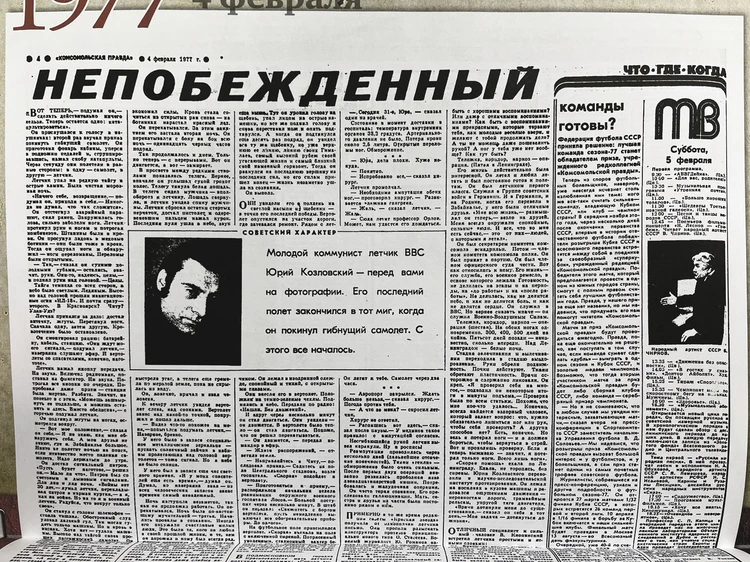

1977

The author of the article we are recalling today is Gennady Nikolaevich Bocharov, known throughout the country as Gek Bocharov, a special correspondent for "Komsomolskaya Pravda" in the 60s and 70s. He traveled to over 60 countries, and his articles later became books, including this essay about the heroic act of military pilot Yuri Kozlovsky. In 1973, during a training flight, Kozlovsky diverted a falling supersonic bomber away from the residential areas of Chita:

“The young communist pilot of the Air Force, Yuri Kozlovsky, is before you in the photograph. His last flight ended at the moment he left the doomed aircraft. That’s where it all began.

“Now, - he thought, - there’s really nothing to be done. Now there’s only one thing left: to eject.”

He listened to the voice in his headphones: a second order to abandon the failing aircraft sounded. He prepared the cockpit light, braced himself against the pedal footrests, and, gathering himself, pulled the ejection handle. In a second, they flew apart: the plane in one direction, the pilot in another.

The pilot landed on sparse taiga and sharp stones. It was a clear, frosty night.

“Wow, what a comeback,” - he thought as he regained consciousness. - “Never thought it would turn out like this.”

He unfastened the emergency parachute and removed his backpack. His head spun, and his legs ached terribly. The pilot reached for his legs and felt his jumpsuit. The pant legs were soaked in blood. He slipped his hand into his fur boots – they were also bloodied. Then he felt his legs and discovered they were broken. The fractures were open.

- Well, he said with dry, cold lips, - at least I still have my arms. I hope they’re intact, - and he raised his arms above his head. – They are.

The taiga grew dark around him, while the sky remained bright. Icy. High above, navigation lights of an IL-18 passed by. And almost immediately – a second one. To Krasnoyarsk? Chita? Ulan-Ude?

The pilot got to work: he pulled out a first aid kit and bandages. He wrapped his legs. First one, then the other. The bleeding was stopped.

He assembled the radio: the battery, cable, and station. “They are waiting for my signal,” - the pilot thought, - “they must be listening to the airwaves. And helicopters with rescuers are certainly on standby.”

The pilot pressed the transmission button. No sound. He turned on the radio beacon and set it to a fixed position. No sound. He pressed all the buttons in turn. He even tried reception – the station was dead. Broken. So, luck had run out there as well. “You can throw it far away, or you can leave it here. As a memorial,” - the pilot thought bitterly.

He tightened the bandages on his legs and looked around.

- Here’s my situation, - he said to himself. - I don’t know how to signal my location. And my friends don’t know where I am. The Transbaikal region is vast. No one will fly out at night for a search if the crash site is unknown. I need to hold on until morning.

He retrieved a signal cartridge. “Better keep it ready,” - he decided. - “You never know.” The cartridge had both light and smoke signals. For day and night. “There hasn’t been a war for 30 years,” - the pilot thought, shifting the cartridge to his jacket pocket, - “yet I feel like I’m in a war. But I am a military pilot. Be glad that it’s just my own people around.”

He removed his helmet – silence enveloped him. His sharpened hearing caught the distant rumble. Only machines could hum like that. But the blood pulsed in his temples. No, it was indeed machines humming. High above the taiga, a passenger plane flew by again. It disappeared, but the hum remained. “That means there’s a road nearby,” - the pilot concluded. - “I need to crawl towards it.”

Movement triggered pain and dizziness. The pain became overwhelming: it tore at his heart and dimmed his vision. The pilot realized that pain was his main enemy, the pain that could make him lose consciousness. “And if I lose consciousness,” - he told himself, - “I won’t make it until morning. The frost will finish me off. I need to crawl.”

The first thing he saw in the morning was a helicopter. The helicopter was coming straight towards him. “Luck is on my side,” - the pilot congratulated himself. He congratulated himself too soon, as it turned out. A gust of wind flattened the orange smoke from the signal cartridge. The smoke did not rise. The sound of the rotors faded.

- Where are you going? - the pilot yelled, pushing his hands against the frozen ground. - Where are you?

On the clear backdrop of the sky, two new helicopters appeared. They flew parallel, low, and silently.

“You guys are looking for me in the wrong place,” - the pilot wanted to say. - “I’m right here and barely hanging on. Come over here.”

But the helicopters disappeared behind the hills.

The author of the essay, Gek Bocharov. Photo: Personal archive of Gennady Bocharov

He crawled again. Suddenly, he heard a vehicle engine revving nearby. The pilot looked to the left and saw a cargo truck behind the tree trunks. It was about 50 meters away. Two men were fiddling with the hood. It was clear they had just started the engine. “There they are, my rescuers,” - the pilot thought and pulled out his pistol. He raised the barrel upwards and fired two rounds in quick succession.

Kozlovsky was found, but the doctors gave him little chance of survival. Both legs were amputated, and he underwent a series of other operations. Yet he survived against all odds. He worked at the Sukhoi Design Bureau, flew again at the age of 68, and at 70, he parachuted. Today, he engages in veteran affairs, and he is 82 years old. Gek Bocharov is 89 years old. Heroes – from the generation of the undefeated.